Broadening the Dialogue: (Re)making the Canadian Nation by Yang Lim

What does Canada mean as a “nation” and what types of discourses are created and disseminated about our country? A number of exhibits in this year’s Works festival deal with this issue in different ways, which include those that the festival has curated and others that have been curated by its partner galleries.

"A Possible Canada" asks visitors to post gratitudes, dreams, visions for a possible Canada.

Amy Loewen’s interactive installation A Possible Canada speaks to the issue of nation by representing a readily identifiable symbol for Canada in an artistic form and by asking the public to think about what they would like to see for Canada’s future. As such, her work engages the public in a dialogue with her artwork as well as with each other, such that their ideas build upon each other and provide inspiration for further discussion. Her installation consists of two parts. The first is her artwork “O’Canada Project” that consists of a maple leaf woven out of rice paper strips, on which there are words identifying values for fostering harmony and relationships in 35 different languages. The second part of her installation includes two notice boards that pose a question about the Canadian nation and invite the public to participate in envisioning what the Canadian nation can become in the future. The board poses the question, “Post your gratitudes, dreams, visions for a possible Canada.” People can write their thoughts on the provided sticky notes and post them on the notice boards; at the same time, they can browse through what others have written. The sharing of ideas become a generator of dialogue and reflection and may even, perhaps, inspire people to action in their own ways in order to work towards that “possible Canada.”

"A Possible Canada" by Amy Loewan, displayed in Edmonton City Hall during The Works 2017

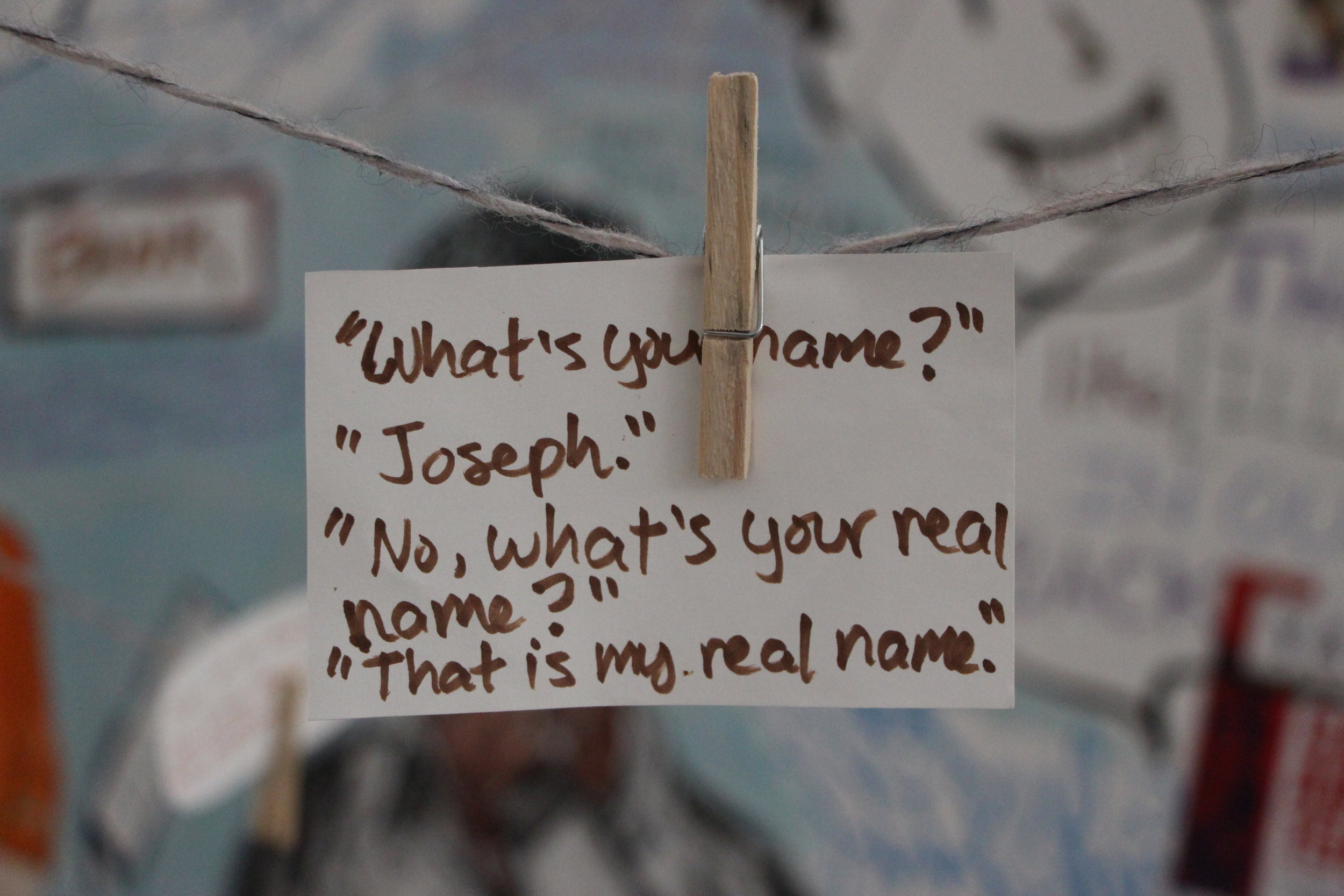

In another sense, the exhibit What Have you Heard About Us? also speaks to the issue of nation by considering the ways in which cultural and political discourses have shaped public perceptions of indigenous and cultural minorities in Canada. Indeed, the concept of “nation” is inextricably linked with issues of identity because its cohesiveness depends on the circulation of predominant narratives that have served to exclude it. This exhibit is a multidisciplinary art installation in which the artist collective ImagiNation Miscellany has created new artwork that explores how Canada’s indigenous and cultural minorities have been represented in stereotypical, reductive, or negative ways that elide the complexity of these peoples’ lives, experiences, and perspectives.

Results of a story circle in 2017, "What have you heard about us?" ImagiNation Miscellany

As a whole, the artwork depicted includes sketches and photos on the exhibit walls as well as installation pieces. For example, there are numerous popular associations with particular items or cultural practices that become identified with particular cultural communities or groups in the mainstream cultural discourses. Two examples of this which are mentioned in the exhibit include martial arts and rice, both of which will likely cause people to think of the Asian community. Although these associations are not invalid, they are problematic if these characteristics become identified as supposedly inherent traits of the group as a whole. For example, not all people of Asian descent know martial arts, yet the representations of Asians in popular culture have perpetuated such associations by portraying Asian characters in rather limited roles: they are depicted as working in laundromats, convenience stores, and restaurants. Even though television shows such as Kim’s Convenience on CBC are a welcome addition because it includes Korean characters, which has not been seen very often on mainstream television, it is still taking place in the recognizable context of a convenience store. As such, this may inadvertently contribute to the same reductive cultural discourses about Asian communities that does not really reflect the diversity of their peoples’ occupations in Canadian society.

In the same way, the representation of the character of Apu Nahasapeemapetilon in The Simpsons is problematic because he has become engrained in the popular imagination as a quintessential South Asian person. As one of the artists has written on one of the exhibit walls, Apu does not represent who he is. It is true that Apu has some positive qualities such as the fact that he has a Ph.D. and harmonious family, but nevertheless he only owns a convenience store and speaks with an accent. Furthermore, the 7-Eleven chain has used his image as a marketing tool to advertise its business, but by highlighting the characters’ qualities that may be stereotypically associated with that cultural community.

"What have you heard about us?" by art collective ImagiNation Miscellany

The exhibit also speaks to other issues that are faced by indigenous and cultural minority communities, such as the fact that the diversity of Canada’s population is not represented in various institutional contexts such as the educational setting. One artist provides two coloured drawings that contrast the predominantly white composition of the Edmonton school staff’s demographics with the cultural diversity of its students. Other artwork in the exhibit evoke the feelings of inadequacy and exclusion that people experience because of their inability to fit into Canadian society, whether this is physically due to their skin colour or the clothes that they wear.

“Grandma’s Garden” by Lynne Howard

The exhibits in the partner galleries also speak to these themes of nationhood and the discourses that have been circulated to promote a national identity. Two notable ones include the ones at the Alberta Craft Council and Latitude 53. The Alberta Craft Council’s fibre art exhibition Women’s Hands: Building a Nation commemorates Canada150 and focuses on women’s achievements. This exhibit exemplifies an assertion and inscription of women’s achievements into Canada’s national narrative, which has historically excluded, marginalized, or trivialized their achievements. In this exhibit, the act of representation functions as a form of agency that is mediated through an art form that may have been associated with domesticity or women’s work. As such, this constitutes an appropriation of that art form in a way that empowers women by using it as a means to affirm their presence and achievements.

“Settler’s Bonnet” by Pat Minton

Critic Sharon Marcus has commented on how fibre work has become more conceptual in recent years due in part to postmodernist influences, which has led to the creation of work that deals with various cultural and political issues. Indeed, the range of work in this exhibit varies from the highly personal to the broadly societal. For example, Lynne Howard’s “Grandma’s Garden” is a highly biographical series that provides an intimate look at the artist’s grandmother, as told through narrative and scenic snapshots associated with her life. In doing so, Howard gives voice to her grandmother’s experiences and recognizes them as an important aspect of Canada’s story. Pat Minton’s “Settler’s Bonnet” also acknowledges her grandmother’s contributions to building the nation in her own way through her personal achievements.

“Do You Know These Famous Canadian Women?” by Ruth Walkden and Rose Brooks-Birarda

In contrast, the quilted work “Do You Know These Famous Canadian Women?” takes a broader societal scope to its subject matter by depicting famous Canadian women who have made an impact on Canada as a whole. Created by Ruth Walkden and Rose Brooks-Birarda, this work portrays several faces of Canadian women who have made their mark on Canada in various ways. These include women in a wide range of disciplines, such as anti-slavery activist, publisher, teacher, lawyer, and journalist Mary Ann Shadd, astronaut Julie Payette, Olympic gold medallist Hayley Wickenheiser, and notable Inuit artist Kenojuak Ashevak, among others. In a similar vein, Sheralee Hancherow’s “Never Give Up” portrays female athletes whose athletic achievements may not have been widely known. For example, her work mentions Chantal Petitclerc. the most decorated athlete in history, and Clara Hughes, who is the only athlete to have obtained multiple medals at both the Summer and Winter Olympics. Other works focus on historical events or developments that have impacted significantly on women’s lives and contributed to their independence and agency, such as Jan Peciulis’s “Women’s Suffrage” and Sharon Johnston and Jennie Wolter’s “The Pill.”

Big'Uns, exhibit by Dayna Danger showing at Latitude 53

In a different sense, Latitude 53’s exhibitions Trumpet and Big‘Uns reflect on Canada as a nation as they draw attention to how national narratives and ideological discourses have excluded or silenced indigenous and other minority perspectives. In Dayna Danger’s Big‘Uns, the life-size photographs of indigenous people constitute a means for individual and collective self-affirmation in two senses: as an affirmation of indigenous identities that have historically been stereotyped, misrepresented, and excluded from narratives of Canadian history, and as an affirmation of people with sexual orientations who continue to be misrepresented, objectified, or omitted from mainstream media. As the exhibit description states, it “explores the act of reclaiming power over our own sexualities and bodies.” Indeed, the use of antlers—associated with male animals—becomes a means for reclaiming a sense of power as they are held by the women in each photo.

Lee Deranger “Reconcile This” and Kazumi Marthiesen “71 Swipes”

The exhibit Trumpet complements Dayna Danger’s work as it includes artwork that questions the contemporary political climate and encourages the public to consider stories and experiences that have been marginalized or excluded. For example, Kazumi Marthiesen’s “71 Swipes” comments critically on the history of American naval bases that are still located in Okinawa, Japan to this day and the sexual crimes that are still committed against Japanese women by American military personnel stationed there. Another work by Lee Deranger, entitled “Reconcile This” highlights how Nova Scotia’s history has failed to recognize indigenous perspectives or fully acknowledge the long-term effects of their mistreatment on indigenous communities today. The work depicts what appear to be three scalps of indigenous women that are tacked against a wooden door, with the Nova Scotian flag set above it, thereby calling attention to the harsh reality of indigenous women who are still murdered or going missing today.

Gerry Yaum photography exhibit at Latitude 53

Similarly, Gerry Yaum’s photographs of impoverished people in Thailand also draw attention to unrecognized stories and experiences that have not typically been part of the mainstream discourse. Despite their economic circumstances, Yaum’s work does not portray them simplistically as powerless victims with which viewers are asked to sympathize. Instead, they are depicted as individuals with dignity and whose lives are not solely defined by their poverty; they are able to make a home for themselves, even though it is located in a garbage dump. This does not discount the reality of their impoverished circumstances, but Yaum’s representation of them avoids stereotyping them as a collective group as his photos depict them as individuals with their own unique personalities and circumstances.

Taken together, these are some of the exhibits in this year’s Works festival that approach the subject of the Canadian nation in their own ways. What can be seen from this artwork is that Canada as a nation is composed not simply of one national narrative, but rather multiple narratives arising out of specific historical, political, and cultural circumstances that are continually in the process of being reconfigured anew by people in the present. It is these narratives and the dialogue generated by them that comprise the ongoing body of stories about Canada.